Mindful Ergonomics II – Practical Application

What Does Mindful Stretch-and-Flex Look Like?

(Make sure to check out Mindful Ergonomics Pt 1 HERE)

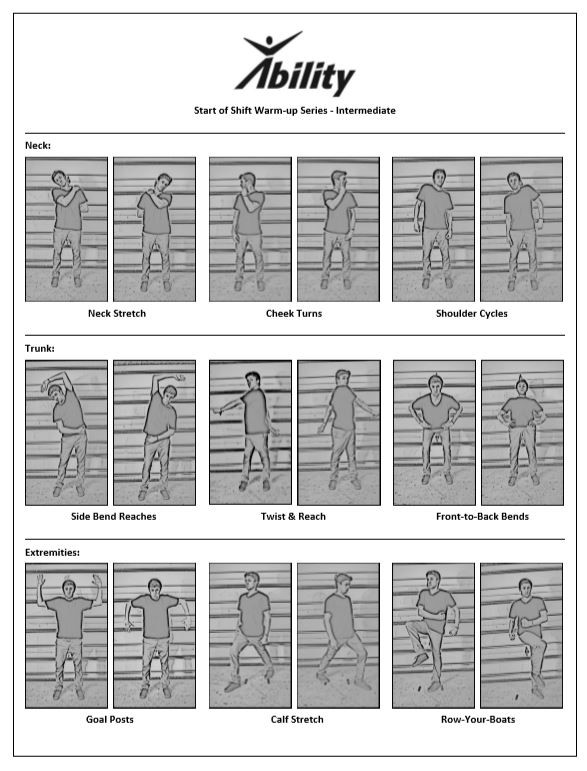

As our example below demonstrates, Mindful Stretch-and-Flex can look very similar to other programs. This simple warmup series only differs in the sense that breathwork is demonstrated and encouraged by the group leader through a conscious effort. Employees are encouraged to exhale with movements outward from the body’s center and inhale with movements returning to its center. This initiates the first steps in recalibrating our nervous system while integrating movement sense. With daily practice, integration solidifies into normal movement and behavioral patterns. This daily repetition is known in neuroscience circles as ‘entrainment’. The adoption, familiarity and coordination of naturally rhythmic and desirable neural frequencies attuned to activities in everyday life.

Without Training, Our Biology Conspires Against Us –

To better understand Mindful Ergonomic applications – ones that can traverse any number of fields, professions and industries – we should review a little basic human biology. Here a tad simplified for easier digestion.

Our nervous system is divided into two large categories. One central (CNS – brain and spinal cord)) the other peripheral (PNS – pretty much everything else). Our peripheral nervous system is further divided into our voluntary somatic nervous system (open and close your fist, for example), and our involuntary (or so we thought) autonomic nervous system.

Our autonomic nervous system (ANS) got its name for being automatic. Internal organs, heartbeat, digestion and breathing and much more can carry on without our constant attention. Face it, if we had to think about every breath, there’d be a lot of dead people lying around. Our ANS keeps us humming along while our minds are off somewhere else.

Our ANS itself is divided into two very distinct branches that work in concert with one another to maintain a steady-state we know as homeostasis – a word that literally means ‘the same place’. Our sympathetic branch of the ANS can be thought of as our accelerator pedal. Its job is to speed things up. Its homeostatic partner is our parasympathetic branch – akin to our brake system – it’s job is to slow things down.

All nervous systems operate on a two-way feedback loop known as afferent (body to brain) and efferent (brain to body) nerves. Our autonomic nervous system (ANS) relies mostly on unconscious input – both internal and external – from within our bodies and from our outer environments.

Internal feedback is provided primarily through a process we call interoception (what our organs are telling us). This is experienced when we notice we’re hungry, for instance. Combined internal and external feedback is brought to us by way of processes called proprioception (what our position sensors are telling us) and kinesthesia (what our movement sensors are telling us) constantly.

Through real-time interaction with our internal and external environments, our CNS / PNS / ANS networks modulate our physiology to attempt to maintain optimum function for the task or situation at hand. All well and good when things operate according to plan. But that’s not always the case, is it?

Where Form Follows Function in Our Biological World –

Here’s where we drill-down into the chemical makeup of our biology. To understand the key players in the relationship between ill-prepared thoughtless reaction, and readily organized mindful response, we need to know the players names.

Chemical messengers allow the sympathetic branch of our ANS to communicate with itself and targets within our bodies. Norepinephrine (aka noradrenaline) and epinephrine (aka adrenaline) can behave as both hormones and neurotransmitters. As hormones, they’re released into the greater bloodstream to slowly turn target organs on and slowly turn them back off.

As neurotransmitters, their function is specifically targeted between one neuron to another. This approach is instantaneous. One can see a two-step front-line (neurotransmitter) and back-line (hormonal) application attributed to each sympathetic branch chemical messenger. Their effects can be both immediate and lingering.

When a quickly reactive situation is called-for, this ‘adrenaline surge’ can bring forth cardiovascular reactivity (among other immediate reactions). This rushes blood, oxygen and nutrients to just about every capillary – and every cell – in our body. Blood pressure immediately jacks up with heart rate. Blood flows to key central organs over less urgent areas.

This cascade results in immediate releases of blood sugar, often resulting in an involuntary ‘tunnel-vision’ presumed to sharpen our immediate focus on present dangers. If left untrained to behave otherwise, this very reaction can cause an unprepared worker to act impulsively rather than respond thoughtfully. A recipe for inappropriate action.

The good news we take away from this biological scenario is drawn from our 21st century approach to medicine. That being the biopsychosocial model. What we now understand is that training or retraining our ANS is a normal part of life. It’s brought about by chance exposure throughout our lifespan. It’s also cultivated by specific volitional practices, such as Mindful Ergonomics for workplace Environmental Health and Safety. Think Mindful Stretch-and-Flex.

Thank Goodness – Through Epigenetics and Neuroplasticity – We’re Trainable

Our new understanding about the interrelatedness between our CNS / PNS / ANS networks offers evidence that we can reconfigure our grey matter through volitional reprogramming. This manual override of the ANS provides a direct path – through afferent and efferent mediation – to more focused, learned responses. Ones that are more appropriate to workplace stressors, whether immediate or longstanding.

This is where our parasympathetic branch of our ANS comes in. The quiet ‘brake’ to our sympathetic ‘accelerator’, our parasympathetic branch can slow our impulsive reactions down enough to let careful, cognitive control retake the wheel. Mindfulness earns its valuable influence into our modern workplace this way. We respond rather than react.

Known on the street as ‘rest-and-digest’, our parasympathetic branch relies on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Its power is called upon through mindful practices like meditation, guided imagery, self-hypnosis – or more approachable practices in the workplace. Here, we mean modernized versions of tai chi and qigong incorporated into Stretch-and-Flex.

Physiological markers that point to influence of the parasympathetic branch include decreases in respiration rate, heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, blood cortisol (the ‘stress hormone’), and the blood catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine. The parasympathetic branch ratchets-down these once believed unreachable physiological functions. Mindful practice makes these functions accessible to individual workers and our entire workforce. We can ‘manually’ override the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The scale tips to our mutual advantage.

All Well and Good – But How Do We Put This Knowledge to Practical Use?

As we discussed last month, modern ‘free-form’ styles of tai chi may be our most accessible, mindful Workforce Stretch-and-Flex option. Participants are encouraged to get into a common ‘groove’ with breath and movement while performing their morning warmups and throughout their workday. That groove is what’s known as ‘the zone’ among elite athletes. Modern tai chi practitioners describe it as ‘flow’. An effortless state where we get out of our own way.

From our biopsychosocial lens, these practices build 1) present moment attention with 2) full awareness, and 3) direct acceptance. Focused attention is better known as concentration. It keeps us on our task at hand. Full awareness is also called ‘open monitoring’. This allows us to observe clearly when our mind is not on task. Acceptance cultivates appropriate action in otherwise stressful situations. Thoughtful responses override thoughtless reactions. The recipe for safer, saner interventions in the 21st century workplace ensues.

The process we use to apply this shift is simply breathwork. Stretch-and-Flex allows opportunity to employ breathwork with movement. Together, they provide a compounded benefit of gaining physical movement with mental clarity. All in the same break. That’s a powerful combination that far exceeds the limiting benefit of conventional Stretch-and-Flex.

Applying this readily available state allows a more focused and settled employee mindset to take over. It produces optimal human functioning among individuals and work groups. The more workers practice this flow state, the more it seeps into everyone’s broader work life. Work itself becomes more centered, safe and sound. Distraction recedes. Concentration deepens. And workforce performance improves.

A safer workplace ensues as calm focus becomes the overriding atmosphere all can notice and experience. Our workforce learns – through practice – how to approach any situation with the intense calm, focused, appropriate action necessary to achieve an optimal outcome. More workers learn to ‘reflect and respond’ than those who would otherwise ‘reflex and react’. This shift is something we’re training to more and more of our corporate clients. It’s a worthy goal for all workplaces.

A little about our author, Matt Jeffs DPT PSM CEAS –

Dr. Jeffs is a health and safety performance advisor for national and international firms. He’s also a seasoned ergonomics educator here at The Back School.

Years ago, he excelled as a big-wave surfer and an experienced ocean lifeguard – with numerous rescues – prior to earning both his undergraduate and doctoral degrees in physical therapy.

He now serves as a Tai Chi Fitness Instructor in multiple settings – including modern healthcare centers and the modern workplace. Through his unique approach to ‘Meta-Physical Therapy’, Mind-Body Awareness is taught, learned, and cultivated into safer, healthier and higher performing work environments.